Psychoactive plants have been used by humans for thousands of years for spiritual and medicinal purposes. The understanding of psychedelics has grown over recent decades as scientific research and public perception have developed and changed.

Ancient Use of Psychedelic Plants

“You know, it’s a funny thing, every one of the bastards that are out for legalizing marijuana is Jewish. What the Christ is the matter with the Jews, Bob? What is the matter with them? I suppose it is because most of them are psychiatrists.”

Potential Uses Include:

Direct (genetic, chemical, and material finds) and indirect (literary, iconographic, and paraphernalia) evidence indicate that psychoactive plants were used for a variety of purposes, including: (1)(4)(5)(6)

Ancient civilizations worldwide seem to have used psychoactive plants for these purposes, including:

Plant Medicine Throughout History

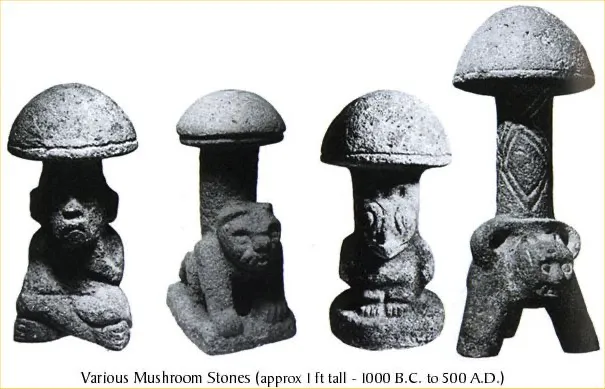

From ritual practices involving peyote in Mesoamerica to the use of Fly-agaric mushrooms in cultures across ancient Asia, humankind has had a strong relationship with plant medicine.(1)(3)

Psilocybin Mushrooms

Peyote (Lophophora williamsii)

The peyote cactus contains mescaline, a hallucinogenic substance. Samples dating back to 3200 BC indicate its use in several prehistoric sites in Northern Mexico and Texas. Cave paintings from 2200-750 BC have been found in these regions, depicting people using the cactus for ceremonial purposes. The Native American Church (NAC) still practices peyote rituals today for social and medicinal purposes, viewing the substance as a religious sacrament that can cleanse the spirit. (1)(12)

Ayahuaszca (Banisteriopsis caapi)

Ayahuasca is a hallucinogenic brew made from the Banisteriopsis caapi vine (containing monoamine oxidase inhibitors) with the leaves of the Psychotria viridis shrub (containing DMT) as well as other ingredients. The exact mix of ingredients in ayahuasca can vary between cultures and practitioners.

Ayahuasca use is believed to originate from the Amazonian basin, where it was used in spiritual ceremonies among various cultures from Brazil to Peru for thousands of years. Ayahuasca use is often practiced in a spiritual context, such as in the Amerindian cultures of Northern Peru, which believes certain plants act as teachers (known as doctores) who can show them how to diagnose and cure illnesses.(1)(6)(13)(14)

San Pedro (Trichocereus)

Archaeological evidence shows the use of the San Pedro cactus (which contains mescaline) for religious and mystical practices in pre-Columbian Andean cultures up to 8600 BC. Religious San Pedro practices are still upheld today in parts of Peru in the form of healing rites intended to cleanse individuals of sickness and evil. (15)

Morning Glory (Ipomoea)

Seeds of the Morning Glory plant contain lysergic acid, an ergot alkaloid and precursor of LSD. There are several plants within this species, although this is the only one with psychoactive properties. Some of the earliest evidence of ipomoea use was found in old wells in Texas and dates back to the Ancient Caddo period (800-1300 AD). Though the Morning Glory seeds discovered were prepared for ingestion, their exact purpose is unknown.(1)

Mandrake (Mandragora)

Henbane (Hyoscyamus)

Henbane contains hallucinogenic alkaloids. Henbane seeds dating back to 6000 BC have been found in Egypt and Spain dating back to 2340 BC. The seeds are believed to have been used to strengthen alcoholic drinks. Hyoscyamus niger, a subspecies known as black henbane, is believed by some scholars to have been used by the Viking berserkers, a warrior group known for their ferocity and resilience on the battlefield. (1)(18)

Henbane can be highly toxic and can cause overheating, delirium, manic episodes, and death. (19)

Jimsonweed (Datura stramonium)

Jimsonweed use can be traced back to Europe and Asia, with samples found in Andorra tracing back to 1700 BC. Its use as a traditional medicine has been documented in China and Tibet as a treatment for asthma, rheumatism, and inflammation. It has also been documented in religious use among indigenous North American tribes. Jimsonweed is also highly toxic and may cause death from cardiovascular issues if consumed in larger amounts.(1)(20)(21)(22)

Water lilies (Nymphaea)

The petals of water lilies may have psychoactive and narcotic properties when ingested. Garlands and bandages on Egyptian mummies dating back to 6000 BC include the petals of water lilies. It is believed the plant was used in Egyptian rituals to gain deep insight and ecstasy among religious leaders. The use of water lilies has also been recorded in Mayan culture for similar purposes, though a different species is used. The two main psychoactive compounds in water lilies are nuciferine, an antipsychotic that induces calmness, and apomorphine, which is a dopamine agonist and can be addictive.(1)(23)(24)

Yopo (Anadenanthera peregrina)

Yopo is a hallucinogenic snuff powder made from the seeds of the tree of the same name. Its use can be traced back to many areas in South America, including pipes in Argentina dating back to 2130 BC containing the tryptamines found in yopo. The Piaroa of Colombia and Venezuela believe that yopo is both the cause of harm and a means of salvation. It is consumed to connect the past to the present and create the future. (1)(25)(26)

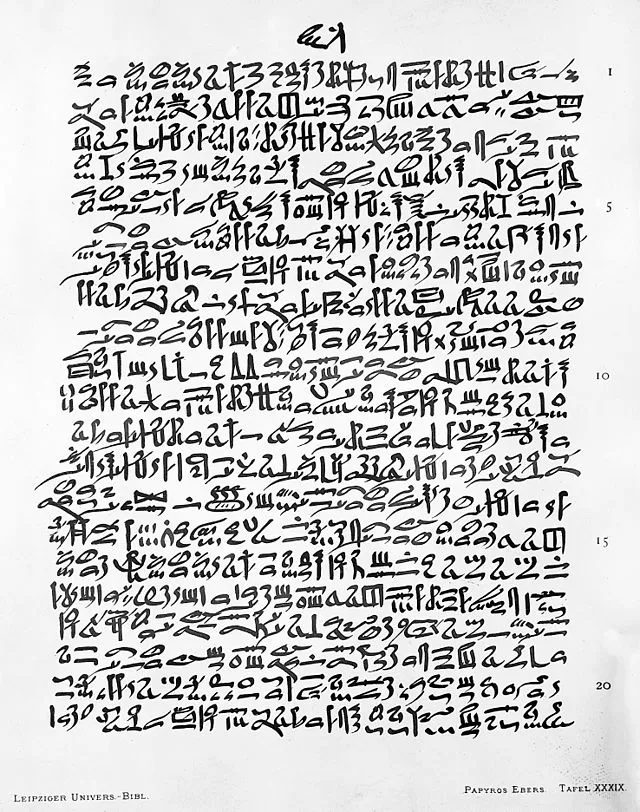

Ergot (Claviceps)

Ergot is a small psychoactive fungus containing lysergic acid, the alkaloid from which LSD was first derived. In Europe in the Middle Ages, many people were killed by ergot that had infested crops. When used in small doses, ergot causes hallucinations, convulsions, and compulsive dancing. This caused it to be associated with witchcraft and the devil. (14)

Fragments of the plant have been found across Europe, including in a temple dedicated to Persephone and Demeter who are both Eleusinian goddesses, contributing to the belief that it was an ingredient in the Eleusinian festival drink of kykeon.(1)

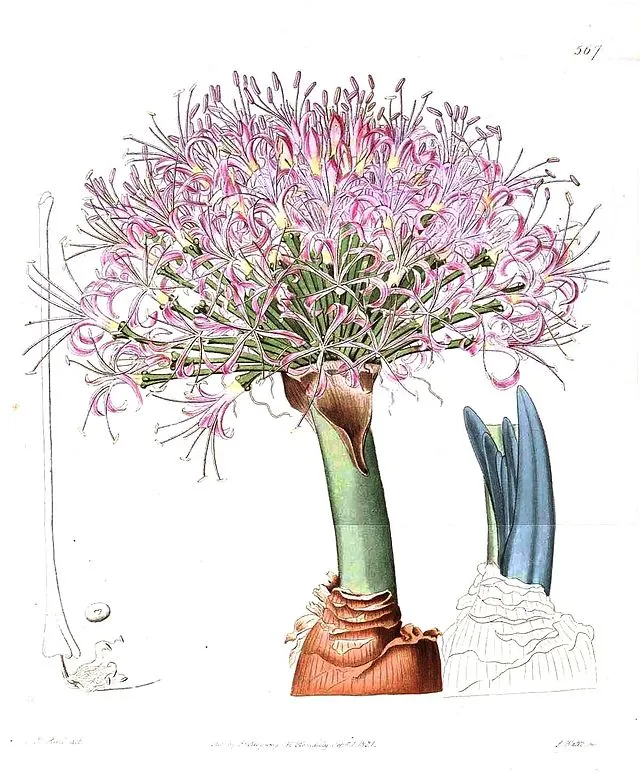

Boophone disticha

Ephedra (Joint Pine)

Ephedra contains the psychoactive alkaloid ephedrine, which has been used in Traditional Chinese Medicine for over 5000 years. Archaeological findings of mummies in China dating back to 2000 BC show the plant’s twigs sewn into fabrics and placed by the bodies.

Its primary use has been linked to treating respiratory conditions such as asthma, bronchitis, and hay fever. Ephedra was still commercially available until 2004, when it was removed due to cases of stroke, heart arrhythmia, and death being linked to it. (1)(28)(29)

Fly-agaric (Amanita Muscaria)

Fly-agaric is a species of large fungus found in Europe, America, and Asia. Accounts of the historical use of the mushroom are varied across different cultures. Some historians believe it to be a primary ingredient in Soma, a brew used by ancient Hindus that would grant immortality by communing with the gods (though some scholars believe the psychoactive ingredient in Soma to be ephedra).(30,31)

In Eastern Europe and Russia, Fly-agaric can be traced to ceremonial use, such as in wedding rituals in parts of Lithuania, and shamanistic practices by the Tungusic people of Siberia. Pictoglyphs of Siberian shamans dating back to 1500-1000 BC have been found, depicting figures with the heads of mushrooms, most likely to be fly-agaric.(1)(32)

Deadly Nightshade (Atropa belladonna)

Deadly nightshade has been used throughout history as a sedating poison, for religious purposes, for its psychoactive properties, and as a beauty product. Small doses create euphoria, hallucinations, and a sensation of flying. Women in Italy used liquid drops to dilate their pupils and increase their attractiveness, hence the name ‘belladonna,’ meaning beautiful woman in Italian. As its name suggests, deadly nightshade is toxic and can cause blurred vision, rashes, headaches, convulsions, and death. (1)(14)(23)

Indigenous Use of Plant Medicine

Indigenous communities have been using psychoactive plants, particularly psilocybin mushrooms, ayahuasca, and peyote, for thousands of years. Many of these practices are believed to originate in the Amazonian basin, extending across indigenous communities throughout the Americas. (6)(13)(15)

However, several tribes native to the United States and parts of Mexico have distinct, indigenous psychedelic practices. In Mexico, one of the most well-known practices involves the use of psilocybin mushrooms, often referred to as teonanácatl, which translates to “flesh of the gods.” These mushrooms have been used in sacred rituals and ceremonies for thousands of years, primarily by the Mazatec (a tribe made famous by Maria Sabina), Mixtec, Nahua, and Zapotec peoples. The consumption of these mushrooms is typically accompanied by specific prayers, songs, and rituals intended to invoke spiritual insights, healing, and communication with divine entities. (6)(13)(15)

Another important aspect of indigenous Mexican psychedelic practices is the use of peyote, a small, spineless cactus containing the psychoactive alkaloid mescaline. Peyote has been traditionally used by the Huichol, Tarahumara, and other native tribes in northern Mexico. The rituals involving peyote, often called hikuri by the Huichol, are rich in symbolism and are conducted as part of a broader spiritual journey. Participants in peyote ceremonies seek guidance, healing, and connection with the natural world and ancestral spirits. These highly structured ceremonies involve a healer who guides the participants through their experiences.(6)(13)(15)

The Salvia divinorum plant, known locally as ska María Pastora, translated as “sage of the diviners” or simply Salvia, is another integral part of indigenous Mexican psychedelic traditions. This plant is primarily utilized by the Mazatec people of Oaxaca. Salvia is traditionally consumed as chewed leaves or tea and used in divination, healing rituals, and religious ceremonies. The effects of Salvia are short-lived but intense, often leading to profound altered states of consciousness and mystical experiences. Like other psychedelic practices, the use of Salvia is deeply embedded in the cultural and spiritual frameworks of the indigenous communities, emphasizing respect for the plant and the spiritual realms it is believed to access.(6)(13)(15)

In the United States, Native American peyote use is most prominently associated with the Native American Church (NAC), which has integrated peyote into its religious ceremonies since the late 19th century. Peyote is used by various tribes, including the Navajo, Comanche, and Kiowa. These ceremonies, often called “Peyote Meetings,” are held overnight in a teepee. Led by a roadman or spiritual leader, the ceremonies involve singing, drumming, prayer, and the communal ingestion of peyote. Participants seek spiritual guidance, healing, and a connection with the Great Spirit. The NAC emphasizes peyote’s sacred nature and its role in promoting peace, morality, and well-being among its members.(6)(13)(15)

In addition to peyote, several Native American tribes have traditionally used other non-psychedelic substances for spiritual and healing purposes. Tobacco use, often in its wild form, is widespread across many tribes. Tobacco is considered a powerful plant that can communicate with the spirit world. It is used in various rituals, including prayer, purification ceremonies, and as an offering to the spirits. The Lakota, for instance, use a ceremonial pipe, or chanunpa, filled with tobacco during important spiritual rituals to send prayers to the Creator.(6)(13)(15)

Typically, the use of these substances would be facilitated by a healer or spiritual leader, who guides the individual or group through the ceremony. The compounds are viewed as sacred and are used to enhance relationships within communities and with the earth, to communicate with spirits and the dead, and to achieve spiritual enlightenment. Many of the traditions continue to be practiced today. (8)(34)

With these practices becoming popular in Western culture, indigenous communities report a misrepresentation, appropriation, and exclusion of their knowledge, culture, and sacred traditions.(34, 35)

Recent research indicates cultural, health, and economic harm to these communities due to: (34)(35)

Western Discovery and Use of Psychedelics

Despite their long history of use in cultures around the world, psychedelics only became a prominent part of Western culture in the early 20th century, after psychedelics like mescaline and LSD were first isolated and synthesized.

| 1897 | German chemist and first chairman of the German Society of Pharmacologists, Arthur Heffter, became the first person to isolate a naturally occurring psychedelic from its plant base when he separated mescaline from peyote.(36) |

| 1912 | MDMA was first synthesized by German research company Merck, Though it wouldn’t gain full notoriety until Alexander Shulgin and his research in the 1970s.(37) |

| 1919 | Mescaline was first synthesized in 1919 by Ernst Späth. |

| 1931 | DMT was first synthesized by a Canadian chemist, Richard Manske, though its hallucinogenic properties were not discovered or researched until 1956.(38) |

| 1936 | 5-Methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (5-MeO-DMT) was first synthesized by Japanese researchers Toshio Hoshino and Kenya Shimodaira in 1936.(39) |

| 1938 | Albert Hofmann, a Swiss chemist, was working with medicinal plants and discovered lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) after isolating and synthesizing compounds found in ergot. (36) |

| 1943 | On April 16th, 1943, Hofmann accidentally consumed a small amount of LSD, documenting feelings of unease and rapid closed-eye hallucinations. On April 19th, on what is now referred to as “Bicycle Day,” Hoffman took a larger amount of LSD, unwittingly going on the world’s first acid trip.(40) He made observational notes of his experience until he lost the power to write, noting feelings of “dizziness, feeling of anxiety, visual distortions, symptoms of paralysis, desire to laugh.” After losing the ability to monitor his experience, he asked his laboratory assistant to take him home by bicycle. Bicycle Day would prove to be the spark for Hofmann’s continued research into LSD. Hofmann experimented with these compounds for years and was involved in the synthesis and investigation of many more psychedelic substances. (36)(41) |

| 1950 | Busch and Johnson published one of the first studies documenting the use of LSD in patients. They administered LSD to 21 individuals suffering from schizophrenia or manic episodes. The study observed that patients were able to re-evaluate the emotional meaning of some of their symptoms and better organize their ideas between reality and fantasized issues.(42) |

| 1953 | The CIA begins its MKUltra project, a series of more than 150 different experiments exploring mind control capabilities. Almost all of these experiments were conducted on unknowing participants, some of which included the use of LSD.(43) While many aspects of the MKUltra experiments remain classified, a 1976 senate hearing concluded that “the nature of the tests, their scale, and the fact that they were continued for years after the danger of surreptitious administration of LSD to unwitting individuals was known, demonstrate a fundamental disregard for the value of human life.”(43) |

| 1955 | R. Gordon Wasson, a mycologist (fungi specialist), was the first to report on the psychedelic properties of mushrooms in Western culture after joining a healing ceremony in Sierra Mazateca, Mexico, led by Maria Sabina. (34) Maria Sabina, a Mazatec sabia (wise woman), allowed Wasson and his wife to attend a healing ritual involving the consumption of psilocybin mushrooms, known as a velada. The purpose of the velada is two parts: one is divination, and the other is to seek healing from an ailment, whether physical or spiritual. (44) The encounter between Gordon Wasson and María Sabina highlights a significant power imbalance. Wasson, a successful banker who became a vice president at J.P. Morgan, had ample resources to fund his expeditions. In contrast, María Sabina, though a revered healer in her community, did not set fixed fees for her mushroom ceremonies. She was compelled to meet with Wasson due to pressure from the municipal trustee of Huautla.(44) In a 1971 interview with Alberto Ongaro, Wasson admitted that the trustee, Don Cayetano, had asked María Sabina to conduct the ceremony, and she felt she couldn’t refuse.(44) Their meeting is considered a pivotal moment in the study of psychedelic plants. However, the coercion María Sabina experienced was later confirmed in a 1976 interview with Álvaro Estrada. She stated, “It is true that before Wasson, no one spoke so freely about children [sacred mushrooms]. None of our people revealed what they knew about this matter. But I obeyed the municipal trustee. However, if the foreigners had arrived without any recommendation, I would also have shown them my wisdom because there is nothing wrong.” (44) |

| 1956 | Hungarian scientist Stephen Szara performs the first series of tests on the hallucinogenic properties of DMT. Szara extracted DMT from the Mimosa hostilis plant and administered it to himself.(45) |

| 1957 | Psychiatrist Humphrey Osmond, along with author Aldous Huxley, coined the term “psychedelics,” which is derived from Greek words meaning “mind” and “manifesting.” (36) |

| 1958 | Albert Hofmann and co-workers first isolated psilocybin and small amounts of psilocin from mushroom samples from Wasson, who had acquired them from his time with the Mazatec. Hoffman reported the synthesis and patent for psilocybin in 1963.(36) |

| 1960 | Harvard psychologists Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert (now known as Ram Dass) founded the Harvard Psilocybin Project. The Harvard Psilocybin Project was established by Leary and Alpert after Leary had visited Mexico and experienced psilocybin for the first time. When he returned to Harvard, he ordered samples of LSD and psilocybin and began organizing experiments with colleagues and students.(47) Leary gained widespread notoriety and would become intrinsically involved with the psychedelic art movement of the time, with notable friends including Allen Ginsberg, LeRoi Jones, Robert Lowell, Willem de Kooning, Dizzy Gillespie, and Jack Kerouac.(47) The Harvard Psilocybin Project would be shut down in 1962 following Leary’s use of psychedelic substances outside of controlled settings and scrutiny of his academic reports. He was fired from Harvard in 1963, leading Leary to move his research project to upstate New York, where his and Alpert’s studies went on unhindered by academic protocol.(47) |

| 1962 | Calvin Stevens, a chemist working for Parke Davis Company, developed an analog of the powerful anesthetic phencyclidine that would go on to be known as ketamine. (48) |

| 1962 | Walter Pahnke conducted the Good Friday experiment (also known as the Marsh Chapel experiment), where he aimed to study and assess the instances and character of psilocybin-induced mystical experiences.(49) The experiment consisted of 20 seminary students, ten of whom were administered 30 mg of psilocybin and the other ten a placebo (200 mg niacin). They then attended the Good Friday sermon at March Chapel and were asked to complete a questionnaire to measure how mystical they found the experience.(49) The questionnaire (given after the experiment and again in a 6-month follow-up) was designed to measure the eight criteria of a mystical experience: introvertive unity, extrovertive unity, transcendence of time and space, deeply felt positive mood, sacredness, objectivity, ineffability, and paradoxicality. Of the group administered psilocybin, 40% recorded what Pahnke deemed a “full mystical experience.”(49) |

| 1963 (- 1976) |

The Spring Grove Experiments, one of the longest-running LSD studies, began in 1963 at the Spring Grove Clinic in Catonsville, Maryland. Initially intended to study the effects of LSD on people with schizophrenia, the Spring Grove Experiments eventually focused on how LSD affects those suffering from addiction, predominantly those with alcoholism. Initial results published in 1967 showed that of the 69 alcoholic patients treated with microdoses of LSD and psychotherapy, 33% remained abstinent six months later, and none suffered any long-term harm.(50) |

| 1964 | Following further research into psychedelic experiences and Buddhist mysticism, Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert released a book titled The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead. The book would further popularize Leary and his work on psychedelics, but it wasn’t until 1966 that Leary began to cement his reputation as the “Pied Piper of LSD.”(47) |

| 1965 | “The Godfather of Ecstasy,” Alexander Shulgin leaves his job at Dow Chemicals to begin research in a shed built in his garden. From here, Shulgin would go on to synthesize over 200 psychoactive compounds over 30 years, including 2C-B and other 2C-x substances, and most famously, ecstasy (though he had not synthesized MDMA or ecstasy, only introduced it to the world of psychology).(51)(52) Shulgin, along with his wife Ann, would later go on to write two books about the beauty of chemistry and substances, PiHKAL and TiHKAL (Phenethylamines and Tryptamines I Have Known And Loved), in 1991 and 1997. Both books are widely regarded as seminal reading for psychedelic and chemistry enthusiasts alike. (52) |

| 1965 | Scottish psychiatrist R.D. Liang established the Philadelphia Association with colleagues looking at alternative treatments for severe mental health conditions such as manic schizophrenia. Liang gained notoriety when he established a treatment center in East London, England, where patients, doctors, and nurses lived together, dubbing it a “safe haven.” Part of Liang’s alternative approach to treatment was administering LSD to patients and staff alike, which would ultimately get him and his center shut down. Though widely criticized for his lack of protocol, Liang’s early LSD research would encourage later psychiatrists to study the substance’s effects on mental health conditions with manic symptoms.(53) |

| The late 1960s | Psychedelic use began to become more prolific outside of artistic and scientific circles, becoming widely synonymous with the hippy movement Beat artists. Musicians famously influenced by their use of psychedelics include The Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, and Pink Floyd. Authors influenced by their psychedelic experiences include Aldous Huxley, William S. Burroughs, and Hunter S. Thompson. (41)(54)(55) However, with increased popularity came scrutiny from the government, law enforcement, the media, and people concerned about the moral implications of psychedelic use. As quickly as LSD and other psychedelics had gained popularity in the early 1960s, the end of the decade would see most of them being placed under the highest legal penalties for possession and distribution.(56) |

The Prohibition of Psychedelics

While acting with transparency in mind, Goddard’s actions led to the seizure of 1.6 million doses of LSD and over 90 arrests. He would later go on record to say that he didn’t want increased pressure from the law to put thousands of young people at risk of serving criminal sentences. (56)

The media’s continued persecution of LSD and other psychedelics, as well as pressure from the Nixon administration, played no small role in creating a “moral panic” that would lead to the majority of these substances being labeled Schedule I substances under the Controlled Substances Act in 1970. This placed them as having the same potential for abuse as heroin and as having no medical benefits.(56)

In 1966, California and New York both created the first criminal laws against unlawful possession of LSD. This, in turn, helped fuel the fire of a “media assault” on LSD, and in April of 1966, James L. Goddard, the then director of the FDA, allowed the media access to their research on LSD.

It should be noted that the Nixon administration’s crusade against psychedelics and cannabis was driven primarily by politics and institutional racism. While the administration publicly centered its campaign on protecting the American way of life, multiple accounts have surfaced over the years indicating that was not the case. Instead, prohibition was weaponized as a means to disenfranchise communities of color, Native Americans, and the anti-war movement.(56)

With prohibition, it became illegal to use, manufacture, cultivate, or distribute psychedelics, thus halting research into their medicinal properties. Though many scientists and researchers did nothing to contest the prohibition of psychedelics, some considered there to be very little evidence of potential harm and considerable evidence of therapeutic benefits, prompting them to advocate for continued scientific exploration.(36)

The Psychedelic Renaissance

In the 1990s, research into the medicinal use of psychedelics began again, albeit tightly regulated due to legal restrictions. Much of this research focused on the medicinal use of psilocybin and LSD, later followed by ketamine, MDMA, DMT, and others. (25)

Much of the research findings have demonstrated therapeutic benefits, and clinical trials of MDMA and psilocybin are moving into advanced approval phases with the Food & Drug Administration (FDA). MDMA is currently undergoing FDA review, with approval possible in August of 2024. However, a recent FDA review panel influenced by an ICER (Institute for Clinical and Economic Review) report has questioned some of the research. It should be noted that the review panel’s recommendation is not binding and has been heavily criticized by both researchers and advocacy groups. (34)(25)

One of the first modern clinical trials using psychedelic substances to treat psychiatric conditions was published by Francisco Moreno and colleagues in 2006. The study was conducted at the University of Arizona and observed the effects of four different doses of psilocybin (25, 100, 200, 300 mcg/kg body weight) on people suffering from treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. (42)

In the decade since Moreno’s initial publication, several other studies have been conducted examining the effects of psychedelics (mainly psilocybin) on a range of psychiatric conditions, such as depression, end-of-life anxiety, and substance use disorder. Studies in Sao Paulo, Brazil, have also trialed the use of a single dose of ayahuasca on patients with recurrent depression. Patients were given 2.2 ml/kg of a standardized preparation of ayahuasca containing 0.8 mg/ml DMT and 0.21 mg/ml of harmine, and their symptoms were measured one day, 1 week, 2 weeks, and 3 weeks after treatment. All patients displayed significant reductions in symptoms in follow-ups until the 2-week mark.(42)

Key figures in the revitalization of psychedelic studies include the late Roland Griffiths, whose research helped prove there is a correlation between prolonged improved mental health and using psilocybin. He also published papers on the benefits of psilocybin in helping those suffering from substance use disorders as well as those facing existential distress caused by life-threatening diseases. His work created prolific interest from investors and philanthropic donors, leading to the creation of the Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research at John Hopkins in 2019.(57)

Another notable figure in helping to revitalize psychedelic research is Rick Doblin and the organization he leads, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS). Doblin has been campaigning for MDMA research since the 1980s, being an outspoken voice against the substance being given a Schedule I classification in 1985.(58)

Since the early 2000s, Doblin and MAPS have been conducting clinical trials for MDMA-assisted therapy, with many studies demonstrating the benefits of the substance for those suffering from PTSD. Recently, MAPS concluded its Phase III clinical trial examining MDMA as a treatment for PTSD and has submitted a new drug application to the FDA, which is expected to issue a decision by August 2024.

As mentioned above, the controversy regarding MAPS methods, as well as allegations of isolated incidents of inappropriate behavior on the part of some researchers, brings the result into question. This has led to a few non-governmental organizations opposing MAPS’ application. Ultimately, the decision rests with the FDA, which is expected to deliver its final say in August 2024.(58)

The Future of Psychedelics & Plant Medicine

Research into plant medicines and psychedelic therapy is still developing, increasing traction and interest among scientific communities and the general public. This has led to Oregon and Colorado passing legislative measures to decriminalize psilocybin and organize regulated access to psilocybin through dedicated healing centers. While psilocybin remains a Schedule I substance and is not yet FDA-approved, this may change in the next few years. (59)(60)

It’s not just psilocybin showing promise for further research and wider application. A trial run by UK biotech company Small Pharma found that a single infusion of DMT, combined with psychotherapy, produced remission in 57% of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) at three months (note: Small Pharma and its DMT trial were acquired by psychedelic biotech firm Cybin Inc in 2023). (61)

As evidence of the potential benefits and relatively low risks of psychedelics grows, it is likely that in the coming years, these substances will become a prominent tool in psychiatric medicine within the decade. However, you must stay engaged and informed and become an active voice supporting psychedelic medicine for the movement to continue. Education and knowledge will continue to be the key to unlocking the future of psychedelic medicine. (35)(36)

Sources

1. Samorini, G. (2019). The Oldest Archeological Data Evidencing the Relationship of Homo Sapiens with Psychoactive Plants: A Worldwide Overview. Journal of Psychedelic Studies, 3(2), 63-80. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1556/2054.2019.008

2. Algerian Cave Paintings Suggest Humans Did Magic Mushrooms 9,000 Years Ago | Open Culture. (n.d.). https://www.openculture.com/2021/01/algerian-cave-paintings-suggest-humans-did-magic-mushrooms-9000-years-ago.html

3. Carod-Artal, F. J. (2015). Hallucinogenic drugs in pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures. Neurología (English Edition), 30(1), 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nrleng.2011.07.010

4. George, D.R., Hanson, R., Wilkinson, D., & Garcia-Romeu, A. (2022). Ancient Roots of Today’s Emerging Renaissance in Psychedelic Medicine. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 46(4), 890–903. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-021-09749-y

5. Chidiac, E.J., Kaddoum, R.N., & Fuleihan, S.F. (2012). Mandragora Anesthetic of the Ancients. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 115(6), 1437-1441. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e318259ee4d

6. Berlant, S. (2005). The Entheomycological Origin of Egyptian Crowns and the Esoteric Underpinnings of Egyptian Religion. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 102(2), 275-88. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2005.07.028

7. Chen, F.P.L. (2021). Hallucinogen Use in China. Sino-Platonic Papers, 318. Retrieved from https://sino-platonic.org/complete/spp318_hallucinogens_china.pdf

8. Hamill, J., Hallak, J., Dursun, S.M., & Baker, G. (2019). Ayahuasca: Psychological and Physiologic Effects, Pharmacology and Potential Uses in Addiction and Mental Illness. Current Neuropharmacology, 17(2), 108–128. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X16666180125095902

9. Mahdihassan, S., & Mehdi, F.S. (1989). Soma of the Rigveda and an Attempt to Identify it. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine, 17(1-2), 1–8. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1142/S0192415X89000024

10. Whale hunting and magic mushroom people of 2,000-year-old Eurasia’s northernmost art gallery. (n.d.). Siberiantimes.com. Retrieved January 16, 2024, from https://siberiantimes.com/other/others/news/whale-hunting-and-magic-mushroom-people-of-2000-year-old-eurasias-northernmost-art-gallery/

11. Ruck, C., & Piper, A. (2011). A Prehistoric Mural in Spain Depicting Neurotropic Psilocybe Mushrooms? Economic Botany. https://www.academia.edu/1376610/A_Prehistoric_Mural_in_Spain_Depicting_Neurotropic_Psilocybe_Mushrooms

12. Prince, M. A., O’Donnell, M. B., Stanley, L. R., & Swaim, R. C. (2019). Examination of Recreational and Spiritual Peyote Use Among American Indian Youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 80(3), 366–370. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2019.80.366

13. Prince, M. A., O’Donnell, M. B., Stanley, L. R., & Swaim, R. C. (2019). Examination of Recreational and Spiritual Peyote Use Among American Indian Youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 80(3), 366–370. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2019.80.366

14. Luna, L. E. (1984). The concept of plants as teachers among four mestizo shamans of iquitos, Northeastern Peru. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 11(2), 135–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-8741(84)90036-9

15. Paredes, A., & Fructuoso Irigoyen-Rascón. (1992). Jikuri, the Tarahumara Peyote Cult: An Interpretation. Springer EBooks, 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-9194-4_12

16. Carod-Artal, F. J., & Vázquez-Cabrera, C. B. (2006). [Mescaline and the San Pedro cactus ritual: archaeological and ethnographic evidence in northern Peru]. Revista de Neurologia, 42(8), 489–498. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16625512/

17. EUROPEAN MANDRAKE: Overview, Uses, Side Effects, Precautions, Interactions, Dosing and Reviews. (n.d.). Www.webmd.com. https://www.webmd.com/vitamins/ai/ingredientmono-1021/european-mandrake

18. Celidwen, Y., Redvers, N., Githaiga, C., Calambás, J., Añaños, K., Chindoy, M. E., Vitale, R., Rojas, J. N., Mondragón, D., Rosalío, Y. V., & Sacbajá, A. (2022). Ethical Principles of Traditional Indigenous Medicine to Guide Western Psychedelic Research and Practice. Lancet Regional Health. Americas, 18, 100410. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2022.100410

19. Fatur, Karsten (2019-11-15). “Sagas of the Solanaceae: Speculative ethnobotanical perspectives on the Norse berserkers”. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 244: 112151. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2019.112151

20. Emboden, W.A. (1981). Transcultural Use of Narcotic Water Lilies in Ancient Egyptian and Maya Drug Ritual. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 3(1), 39-83. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-8741(81)90013-1

21. Mai Et Al, Steroidal saponins from Datura metel. Steroids. 2017;121:1-9. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2017.02.002.

22. Krishna Murthy B, Nammi S, Kota MK, Krishna Rao RV, Koteswara Rao N, Annapurna A. Evaluation of hypoglycemic and antihyperglycemic effects of Datura metel (Linn.) seeds in normal and alloxan-induced diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004; 91(1):95-8.

23. Soni, P., Siddiqui, A. A., Dwivedi, J., & Soni, V. (2012). Pharmacological properties of Datura stramonium L. as a potential medicinal tree: An overview. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine, 2(12), 1002–1008. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2221-1691(13)60014-3

24. Emboden, W.A. (1981). Transcultural Use of Narcotic Water Lilies in Ancient Egyptian and Maya Drug Ritual. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 3(1), 39-83. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-8741(81)90013-1

25. Blue Lotus Flower: Uses, Benefits, and Safety. (2020, September 25). Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/blue-lotus-flower#what-it-is

26. Rodd, R. (2002). Snuff Synergy: Preparation, Use and Pharmacology of Yopo and Banisteriopsis Caapi Among the Piaroa of Southern Venezuela. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 34(3), 273–279. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2002.10399963

27. Rodd, R., & Sumabila, A. (2011). Yopo, Ethnicity and Social Change: A Comparative Analysis of Piaroa and Cuiva Yopo Use. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 43(1), 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2011.566499

28. Neergaard, J. S., Andersen, J., Pedersen, M. E., Stafford, G. I., Staden, J. V., & Jäger, A. K. (2009). Alkaloids from Boophone disticha with affinity to the serotonin transporter. South African Journal of Botany, 75(2), 371–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2009.02.173

29. Guerra-Doce, E., Rihuete-Herrada, C., Micó, R., Risch, R., Lull, V., & Niemeyer, H.M. (2023). Direct Evidence of the Use of Multiple Drugs in Bronze Age Menorca (Western Mediterranean) from Human Hair Analysis. Scientific Reports, 13, 4782. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31064-2

30. Ephedra Information | Mount Sinai – New York. (n.d.). Mount Sinai Health System. https://www.mountsinai.org/health-library/herb/ephedra

31. Barrett, F. S., & Griffiths, R. R. (2017). Classic Hallucinogens and Mystical Experiences: Phenomenology and Neural Correlates. Behavioral Neurobiology of Psychedelic Drugs, 36, 393–430. https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2017_474

32. Mahdihassan, S., & Mehdi, F. S. (1989). Soma of the Rigveda and an Attempt to Identify It. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine, 17(01n02), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1142/s0192415x89000024

33. Wasson, R. Gordon (1980). The Wondrous Mushroom: Mycolatry in Mesoamerica. McGraw-Hill. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-07-068443-0.

34. Deadly nightshade | The Wildlife Trusts. (n.d.). Www.wildlifetrusts.org. https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/wildlife-explorer/wildflowers/deadly-nightshade

35. Williams, K., González Romero, O.S., Braunstein, M., & Brant, S. (2022). Indigenous Philosophies and the “Psychedelic Renaissance”. Anthropology of Consciousness, 33(2), 506-527. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/anoc.12161

36. Celidwen, Y., Redvers, N., Githaiga, C., Calambás, J., Añaños, K., Chindoy, M. E., Vitale, R., Rojas, J. N., Mondragón, D., Rosalío, Y. V., & Sacbajá, A. (2022). Ethical Principles of Traditional Indigenous Medicine to Guide Western Psychedelic Research and Practice. Lancet Regional Health. Americas, 18, 100410. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2022.100410

37. Rucker, J.J.H., Iliff, J., & Nutt, D.J. (2018). Psychiatry & the Psychedelic Drugs. Past, Present & Future. Neuropharmacology, 142, 200-218. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.12.040

38. Freudenmann, R. W., Öxler, F., & Bernschneider-Reif, S. (2006). The origin of MDMA (ecstasy) revisited: the true story reconstructed from the original documents. Addiction, 101(9), 1241–1245. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01511.x

39. Barker, S. A. (2018). N, N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), an Endogenous Hallucinogen: Past, Present, and Future Research to Determine Its Role and Function. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12(536). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00536

40. Ermakova, A. O., Dunbar, F., Rucker, J., & Johnson, M. W. (2021). A narrative synthesis of research with 5-MeO-DMT. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 36(3), 273–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/02698811211050543

41. Bicycle Day’s Dilemma From the writings of Albert Hoffmann. (n.d.). https://www.uvic.ca/research/centres/cisur/assets/docs/iminds/bicycle-hdt.pdf

42. Nichols, D.E. (2016). Psychedelics. Pharmacological Reviews, 68(2), 264–355. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.115.011478

43. Rucker, J. J. H., Iliff, J., & Nutt, D. J. (2018). Psychiatry & the psychedelic drugs. Past, present & future. Neuropharmacology, 142, 200–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.12.040

44. Eschner, K. (2017, April 13). What We Know About the CIA’s Midcentury Mind-Control Project. Smithsonian; Smithsonian.com. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/what-we-know-about-cias-midcentury-mind-control-project-180962836/

45. María Sabina, Mushrooms, and Colonial Extractivism. (2021, May 27). Chacruna. https://chacruna.net/maria-sabina-mushrooms-and-colonial-extractivism/

46. Barker, S. A. (2018). N, N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), an Endogenous Hallucinogen: Past, Present, and Future Research to Determine Its Role and Function. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12(536). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00536

47. Psilocybin. (2017, October 2). American Chemical Society. https://www.acs.org/molecule-of-the-week/archive/p/psilocybin.html

48. Witt, E. (2018, May 29). The Psychedelic Renaissance: Trip Reports from Timothy Leary, Michael Pollan, and Tao Lin. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/books/under-review/the-science-of-the-psychedelic-renaissance

49. Li, L., & Vlisides, P. E. (2016). Ketamine: 50 Years of Modulating the Mind. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10(612). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00612

50. Barrett, F. S., & Griffiths, R. R. (2017). Classic Hallucinogens and Mystical Experiences: Phenomenology and Neural Correlates. Behavioral Neurobiology of Psychedelic Drugs, 36, 393–430. https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2017_474

51. Yensen, Richard & Dryer, Donna. (1992). Thirty Years of Psychedelic Research: The Spring Grove Experiment and Its Sequels. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309477954_Thirty_Years_of_Psychedelic_Research_The_Spring_Grove_Experiment_and_Its_Sequels

52. 2C-B – an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. (n.d.). Www.sciencedirect.com. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/2c-b

53. How did Alexander Shulgin become known as the Godfather of Ecstasy? (2014, June 3). The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/shortcuts/2014/jun/03/alexander-shulgin-man-did-not-invent-ecstasy-dead

54. O’Hagan, S. (2012, September 1). Kingsley Hall: RD Laing’s experiment in anti-psychiatry. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/sep/02/rd-laing-mental-health-sanity

55. O’Brien, L.M. (Updated 2023). Psychedelic Rock. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/art/psychedelic-rock

56. Dickins, R.J. (2012). The Birth of Psychedelic Literature. University of Exeter. Retrieved from https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/bitstream/handle/10036/4207/DickinsR.pdf

57. Stanger, A. (2021). “Moral Panic” in the Sixties: The Rise and Rapid Declination of LSD “Moral Panic” in the Sixties: The Rise and Rapid Declination of LSD in American Society in American Society. https://ir.library.louisville.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1072&context=tce

58. Roland Griffiths, Pioneering Psychedelic Researcher, Dies. (n.d.). Www.hopkinsmedicine.org. Retrieved January 16, 2024, from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/newsroom/news-releases/2023/10/roland-griffiths-pioneering-psychedelic-researcher-dies

59. Nickles, L. K. R., David. (2022, May 11). The Trials of Rick Doblin. The Cut. https://www.thecut.com/article/mdma-psychotherapy-research-rick-doblin.html

60. Colorado voters legalize psilocybin and psychedelic therapy. (2022, November 9). The Denver Post. https://www.denverpost.com/2022/11/08/colorado-results-prop-122-legalizing-psilocybin-psilocin-mushrooms/

61. The Intercept. (n.d.). Biden Administration Plans for Legal Psychedelic Therapies Within Two Years. The Intercept. https://theintercept.com/2022/07/26/mdma-psilocybin-fda-ptsd/

62. Major study on DMT shows promise for depression. (n.d.). European Pharmaceutical Review. https://www.europeanpharmaceuticalreview.com/news/178880/major-study-on-dmt-shows-promise-for-depression/

63. Ketamine plus therapy could help treat alcoholism, say researchers. (2022, December 13). The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2022/dec/13/ketamine-plus-therapy-could-help-treat-alcoholism-research

Edmund Murphy

Edmund Murphy Morgan Blair, MA, LPC

Morgan Blair, MA, LPC